Every time I build a web app, I worry about a bunch of basic things (persisting data, knowing when to compute which things, keeping things working smoothly and reliably across reboots / crashes / redeployments / scaling / page reloads, etc, running scheduled one-time or – god forbid! – recurring things reliably, keeping my code simple and maintainable, understanding the history of user’s interactions with the app, and general stats, etc.)

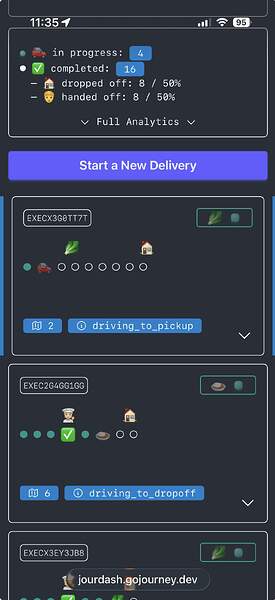

I got tired of doing this over and over again, and I built a package, Journey, which, backed by Postgres-based persistence, provides these things. This made my web applications extremely simple and easy to build, run, and maintain. And! No additional infrastructure or online service subscription is required – it’s just my application and my postgres database!!

I thought I would publish the package, and share it here, in case anyone else finds this useful, or has any thoughts or feedback, or interesting use cases,

With Journey, the code of my apps is cleanly split into 1. “business logic” (the functions that do things, e.g. compute horoscopes, send emails or texts, make credit approval decisions, etc.), AND 2. the graph defining the flow of the application.

Then my liveview (for example) creates graph executions for users that go through the flow, and use those executions to save user-supplied values, and to read computed values to be rendered.

I put together a tiny liveview demo website that “computes” your “horoscope” (https://demo.gojourney.dev/), together with its source (GitHub - shipworthy/journey-demo). Notice how thin the liveview component is, esp given how “state-rich” the web page is.

If you just want a quick glance, here is an over-simplified (no scheduling, no clearing “PII”) version that captures its essence:

- the “business logic”:

defmodule MyBusinessLogic do

def compute_zodiac_sign(%{month: month, day: day}) do

IO.puts("compute_zodiac_sign: month: #{month}, day: #{day}")

my_sign = "Pisces"

{:ok, my_sign}

end

def compute_horoscope(%{zodiac_sign: zodiac_sign, first_name: first_name}) do

IO.puts("compute_horoscope: zodiac_sign: #{zodiac_sign}, first_name: #{first_name}")

horoscope = "#{first_name}, as a #{zodiac_sign}, you are skeptical of horoscopes. Expect a lovely surprise."

{:ok, horoscope}

end

end

- the graph defining the application’s inputs, computations and dependencies.

defmodule MyGraph do

import Journey.Node

def graph() do

Journey.new_graph(

"tiny horoscope example",

"v1.0.98",

[

input(:first_name),

input(:month),

input(:day),

compute(

:zodiac_sign,

[:month, :day],

&MyBusinessLogic.compute_zodiac_sign/1

),

compute(

:horoscope,

[:first_name, :zodiac_sign],

&MyBusinessLogic.compute_horoscope/1

)

],

f_on_save: fn execution_id, node_name, {:ok, result} ->

IO.puts("f_on_save: '#{execution_id}' value computed and saved: '#{node_name}' '#{result}'")

# Notify the liveview.

# Phoenix.PubSub.broadcast(...)

end

)

end

end

- executing instances of the graph

When a user interacts with the web page, my Liveview creates a graph’s execution for the user’s visit, sets inputs to it, and reads and renders computed values.

iex(3)> execution = Journey.start_execution(MyGraph.graph()); :ok

:ok

iex(4)> execution = Journey.set_value(execution, :day, 10); :ok

:ok

iex(5)> execution = Journey.set_value(execution, :month, 3); :ok

compute_zodiac_sign: month: 3, day: 10

:ok

f_on_save: 'EXECYJ43AG4X6HM3RJ518651' value computed and saved: 'zodiac_sign' 'Pisces'

iex(6)> execution = Journey.set_value(execution, :first_name, "Mario"); :ok

compute_horoscope: zodiac_sign: Pisces, first_name: Mario

:ok

f_on_save: 'EXECYJ43AG4X6HM3RJ518651' value computed and saved: 'horoscope' 'Mario, as a Pisces, you are skeptical of horoscopes. Expect a lovely surprise.'

iex(7)> Journey.values(execution)

%{

month: 3,

day: 10,

last_updated_at: 1755848525,

execution_id: "EXECYJ43AG4X6HM3RJ518651",

zodiac_sign: "Pisces",

first_name: "Mario",

horoscope: "Mario, as a Pisces, you are skeptical of horoscopes. Expect a lovely surprise."

}

If this sounds interesting to anyone, I am very interested in hearing your thoughts, questions, feedback, comments, use cases.

Here is where you can find journey:

Hexpm: Journey v0.10.27 — Documentation

Github repo: GitHub - markmark206/journey

Demo website: https://demo.gojourney.dev/

Demo website source: GitHub - shipworthy/journey-demo

Thank you!

Mark.

PS When thinking about sharing Journey, I decided to play with a dual-license approach (free for projects with revenues under US$10k/month, with a small build key fee for other uses). I am curious if this might be an interesting approach for other current or future library developers, who might want to contribute to the Elixir (or some other) ecosystem, but are protective of their uncompensated time. If anyone has thoughts / questions / feedback on this, I am very interested to hear it!

PPS While the source code for the package is available, the dual-license approach means that this is not OSS, so I am posting it here, rather than in “Libraries”.