I think we’re in agreement here, but the tech leader should, IMO, be happy to justify, in detail, their choice of web framework or any significant technology choice to a mentor or investor and how it aligns with the budget and the nature of risk the organisation is willing to take on. Here’s what has shaped my opinion…

I’ve been a developer, tech lead, business founder, investor and business advisor (mostly in software technology for heavy industry), and I have seen multiple major car crashes from very smart tech leaders resulting in zero feature delivery for 18+ months 3-4 years down the track. (All due to overcomplicating things FWIW.)

I would absolutely be wanting a very robust discussion with any tech leader on the architectural and philosophical approaches they choose to take (particularly if I didn’t directly hire them), as poor choices can break the company.

That’s not to say I would impose my preferred tech stack on a tech leader - I don’t and I wouldn’t - but I do want to ensure they can explain the long-term consequences of their decision-making. The role of a mentor/investor/company director in this case is not to micro-manage, but to ask the hard questions of how things look 5 years down the track, what does the total cost of ownership look like and what drives it, how the understanding of the system will be maintained in corporate memory, how is complexity assessed, what range of support skills will be required, how developers will be onboarded, what is the level and nature of vendor lock-in, what kind of trade-off analysis is performed when pulling in dependencies, compliance with regulatory obligations, what level of independent thought has been exercised vs doing whatever FB & Google do with their multi-$B R&D budgets, etc. The framing of questions would obviously change depending on the context of the company.

If this is done in the right way, with mutual respect etc etc, it is the way to build two-way trust and understanding. You don’t just hire a manager and immediately totally trust them - that’s not how it works unless you have worked with them already for a number of years. And as a newly hired manager, you don’t just “know” what’s important to a particular company - going through the process of justifying and refining is part of the process of learning what’s important (and also whether the owners are generally sensible or not and whether you want to hang around  )

)

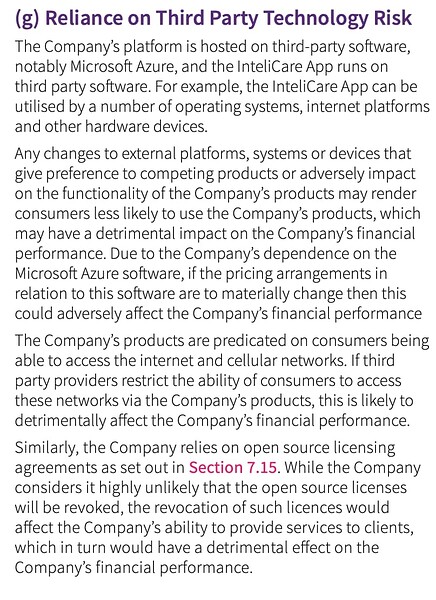

There is a difference between supervision and oversight. And from an oversight perspective, it is their business to understand potential risks and costs introduced by a particular tech stack. As a common example, if you are raising funds in a public market, you must disclose potential risks specific to your company. This is definitely a board level and investor concern. Here’s an extract from the prospectus for a recent-ish software IPO (ASX:ICR). Vendor lock-in to Azure, a tech-stack decision, gets a special mention:

Investors require oversight (either directly for small companies or through a board of directors for large companies). For tech companies, this means satisfying themselves that the tech decision-making is in the interests of the shareholders and other stakeholders, and that means having these robust discussions with the individuals tasked with the decision-making. Directors leave themselves open to legal action from investors if they can not demonstrate that they have taken reasonable steps to manage key risks to the organisation, or if the risk profile of the organisation is materially different to that previously communicated to investors.

It’s no different to other roles - directors directly engage with the CFO to understand the risks & controls in place, and engage external auditors in addition to ensure the CFO or their regional representatives aren’t redirecting tax office payments into their personal accounts (or whatever else). And yes, they may tread on toes - e.g. pushing the CFO to implement a compliance system. They engage with the CMO to understand the marketing programme and often-times ask the next level down to explain how marketing spend represents value-for-money. They engage with the CPO and individual product managers to check-in on the implementation of product strategy. Internal control models (e.g. as described in Sarbanes-Oxley) encourage directors to regularly receive information from individuals below executive management levels to ensure an unrealistically rosy picture is not being painted by the execs.

People’s personal circumstances can drive them to do things that they may not do otherwise (e.g. a life event leading to well-hidden drug or alcohol addiction which then impairs the clarity of their thinking - maybe it’s just Australia, but I’ve seen this 3-4 times now), so this oversight, while more intense up front, does need to be ongoing.

Finally, for me personally, when I am in a tech leadership role there is nothing more demoralising than zero interest in tech strategy & approach from up on high.

Well this turned into a bit of an essay! Hopefully it’s useful.